Finding Rizal, the First Filipino

To foretell the destiny of a nation, it is necessary to open the book that tells of her past.– Dr. José Rizal

Chicago. July 5.

Trying to keep my hands at ten and two, I scan the horizon: the full, green trees, the low benches, and the fencing and aluminum barriers that divide Lake Shore Drive from the narrow strip of parkland to its west, and back to the road before me. Driving north on Marine Drive, parked cars choke either side. School is out and a techno bass line thunders out from a music festival at nearby Montrose Beach.

As I passed a medical center to my left, a clearing appears on the right, and there he is. Doctor José Rizal. Well, his statue.

Luckily before I hit Lawrence Avenue, a parking spot opens up. The Chicago Rizal statue is green, like the Statue of Liberty. He blends right in.

Through the dewy grass I walk to José. Rizal is the Philippines' national hero. He was a physician, historian, critic of clergy abuses, novelist, polyglot, intellectual, world traveler and martyr. In towns big and small across the archipelago, main streets are named for Rizal. Plazas may boast a bust or statue of his likeness; murals depict his execution or a bit from his oft-quoted poetry. All secondary school students read his dual critique of the clergy’s abuses - Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Social Cancer). December 30, the day of his martyrdom, is a national holiday. An order of knights over 100 years old and with members across the globe bears his name and is dedicated to disseminating his teachings.

Wili Buhay, member of the order of the Knights of Rizal and a leader of the Filipino American Historical Society’s local chapter shared the statue’s history. In the late 1990s Filipino communities across the globe, Chicago notwithstanding, prepared to celebrate the centennials of Dr. Rizal’s birth (1996) and of the Philippine Republic (1998).

The statue, by artist Antonio T. Mondejar, was unveiled on Rizal’s 138th birthday, June 19, 1999.

“After all this time, we are still discovering Rizal.”

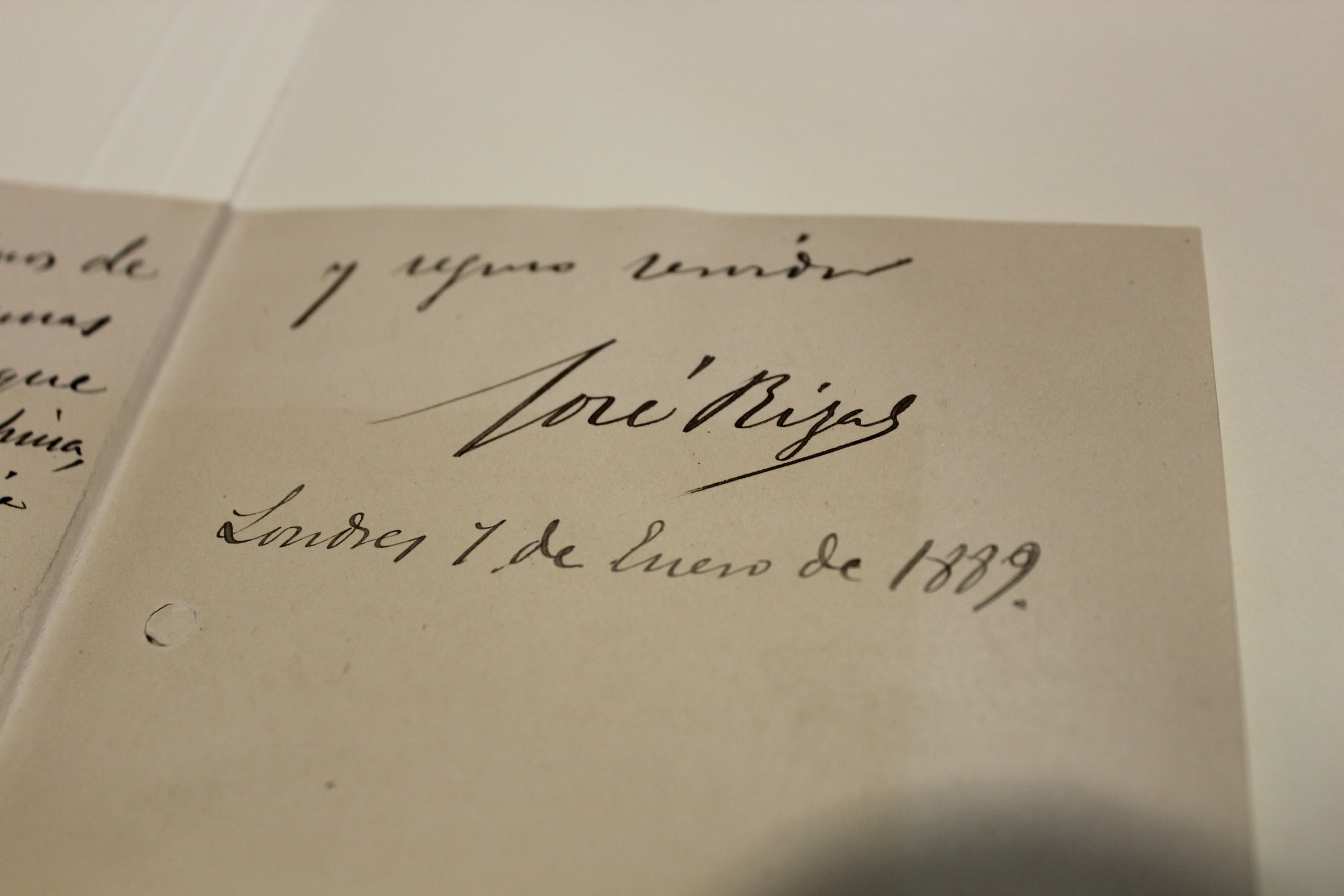

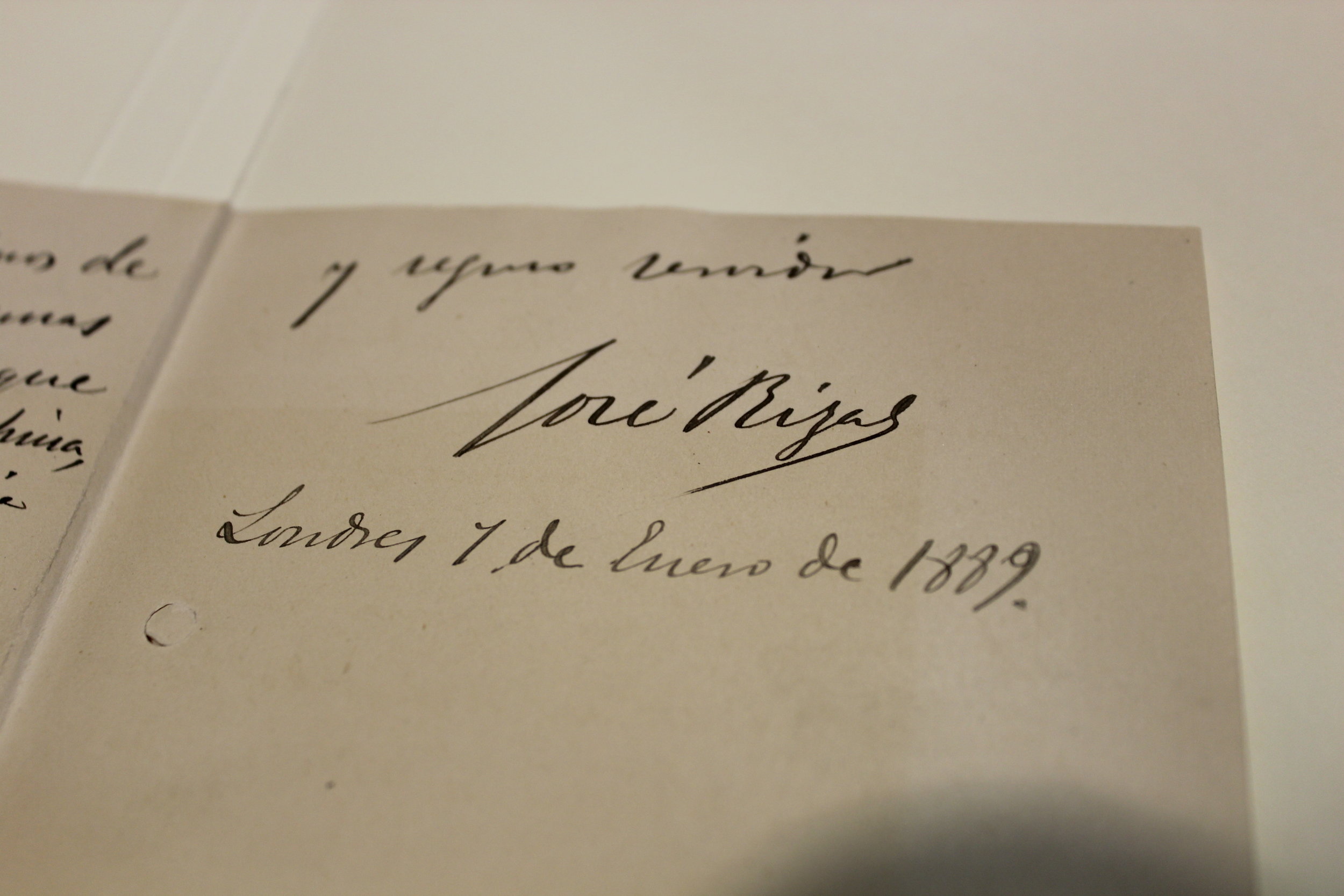

“He was executed by the Spanish at 35 years old. In those days, one would risk being hunted by the Spanish Crown if you owned books written by Rizal.” Wili said that many other relics -- long forgotten in museum storage, in family attics -- still are coming to light.

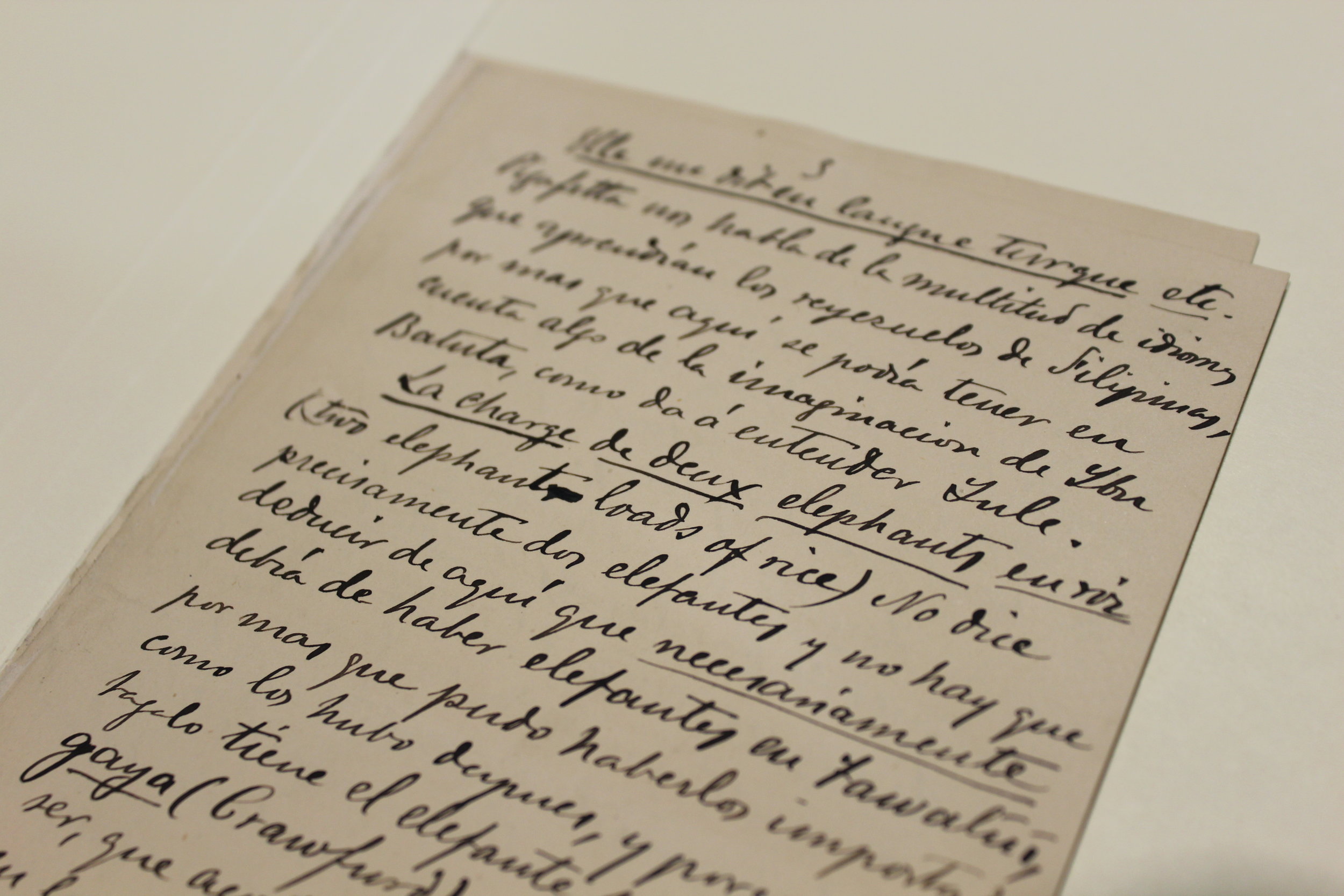

Wili told me about his uncle, an historian, who was sent to Madrid in the 1950s to research and document the oral history of Rizal. Rizal spoke many languages and his writings survive on in Tagalog, Spanish and French – often he interchanged them in the same paragraph! As translations and their interpretations vary and newer generations of scholars and enthusiasts discover Rizal anew, his history (and the history of the Filipino people) lives and moves.

Back at the statue, I snapped a few pictures. A few flower vases were tipped over at the base of the statue, their contents long wilted and making their way back to earth.

That overcast day, I decide to return to the statue after dark. The Filipino and United States flags flank the statue, and the mounted floodlights could prove a more dramatic picture, I thought.

Well after dusk, the lights were not turned on.

Note: Posts in this series are sponsored by the Philippines' Department of Tourism (DOT). The 2013 Ambassadors' Tour was in July 2013, and the Philippines' DOT underwrote my participation.

Biblio and References

Filipinas dentro de cien años (The Philippines within a century). Dr. Jose Rizal. La Solidaridad, September 1889 – February 1890. Quote above cited in Meaning and History: The Rizal Lectures, Dr. Ambeth Ocampo. Anvil Press, Manila: 2011.

Chicago Park District information sheet on the Rizal Statue [PDF], 2010.

Knights of Rizal: History of the Dr. Jose Rizal Monument in Chicago.

Philippine manuscripts of the Ayer Collection, The Newberry Library, Chicago.